Call me EMO, but at least I'm a good writer!

Eto...this is all my writings and work...pls, hold your applause and praise...=p

SYEMPRE andito si NOLI, pero wala pa nung MYX at wala pa nung MTV...pero sinulat ko ang NOLI!

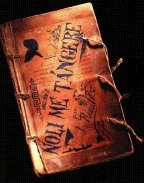

Noli Me Tangere

"My proposal on the book," he wrote on January 2, 1884, "was

unanimously approved. But afterwards difficulties and objections were raised

which seemed to me rather odd, and a number of gentlemen stood up and refused

to discuss the matter any further. In view of this I decided not to press it

any longer, feeling that it was impossible to count on general support…"

"Fortunately," writes one of Rizal’s biographers, the anthology, if

we may call it that, was never written. Instead, the next year, Pedro Paterno

published his Ninay, a novel sub-titled Costumbres filipinas (Philippines

Customs), thus partly fulfilling the original purpose of Rizal’s plan. He

himself (Rizal), as we have seen, had ‘put aside his pen’ in deference to the

wishes of his parents.

But the idea of writing a novel himself must have grown on him. It would be no

poem to forgotten after a year, no essay in a review of scant circulation, no

speech that passed in the night, but a long and serious work on which he might

labor, exercising his mind and hand, without troubling his mother’s sleep. He

would call it Noli Me Tangere; the Latin echo of the Spoliarium is not without

significance. He seems to have told no one in his family about his grand

design; it is not mentioned in his correspondence until the book is well-nigh

completed. But the other expatriates knew what he was doing; later, when

Pastells was blaming the Noli on the influence of German Protestants, he would

call his compatriots to witness that he had written half of the novel in

"From the first," writes Leon Ma. Guerrero, Rizal was haunted by the

fear that his novel would never find its way into print, that it would remain

unread. He had little enough money for his own needs, let alone the cost of the

Noli’s publication… Characteristically, Rizal would not hear of asking his

friends for help. He did not want to compromise them.

Viola insisted on lending him the money (P300 for 2,000 copies); Rizal at first

demurred… Finally Rizal gave in and the novel went to press. The proofs were

delivered daily, and one day the messenger, according to Viola, took it upon

himself to warn the author that if he ever returned to the

The printing apparently took considerably less time than the original estimate

of five months for Viola did not arrive in

Rizal, himself, describing the nature of the Noli Me Tangere to his friend

Blumentritt, wrote, "The Novel is the first impartial and bold account of

the life of the tagalogs. The Filipinos will find in it the history of the last

ten years…"

Criticism and attacks against the Noli and its author came from all quarters.

An anonymous letter signed "A Friar" and sent to Rizal, dated

February 15, 1888, says in part: "How ungrateful you are… If you, or for

that matter all your men, think you have a grievance, then challenge us and we

shall pick up the gauntlet, for we are not cowards like you, which is not to

say that a hidden hand will not put an end to your life."

A special committee of the faculty of the

On December 28, 1887, Fray Salvador Font, the cura of Tondo and chairman of the

Permanent Commission of Censorship composed of laymen and ordered that the

circulation of this pernicious book" be absolutely prohibited.

Not content, Font caused the circulation of copies of the prohibition, an act

which brought an effect contrary to what he desired. Instead of what he

expected, the negative publicity awakened more the curiosity of the people who

managed to get copies of the book.

Assisting Father Font in his aim to discredit the Noli was an Augustinian friar

by the name of Jose Rodriguez. In a pamphlet entitled Caiingat Cayo (Beware).

Fr. Rodriguez warned the people that in reading the book they "commit

mortal sin," considering that it was full of heresy.

As far as

It is well to note that not detractors alone visibly reacted to the effects of

the Noli. For if there were bitter critics, another group composed of staunch

defenders found every reason to justify its publication and circulation to the

greatest number of Filipinos. For instance, Marcelo H. Del Pilar, cleverly

writing under an assumed name Dolores Manapat, successfully circulated a

publication that negated the effect of Father Rodriguez’ Caiingat Cayo, Del

Pilar’s piece was entitled Caiigat Cayo (Be Slippery as an Eel). Deceiving

similar in format to Rodriguez’ Caiingat Cayo, the people were readily

"misled" into getting not a copy o Rodriguez’ piece but Del

Pillar’s.

The Noli Me Tangere found another staunch defender in the person of a Catholic

theologian of the Manila Cathedral, in Father Vicente Garcia. Under the

pen-name Justo Desiderio Magalang. Father Garcia wrote a very scholarly defense

of the Noli, claiming among other things that Rizal cannot be an ignorant man,

being the product of Spanish officials and corrupt friars; he himself who had

warned the people of committing mortal sin if they read the novel had therefore

committed such sin for he has read the novel.

Consequently, realizing how much the Noli had awakened his countrymen, to the

point of defending his novel, Rizal said: "Now I die content."

Fittingly, Rizal found it a timely and effective gesture to dedicate his novel

to the country of his people whose experiences and sufferings he wrote about,

sufferings which he brought to light in an effort to awaken his countrymen to

the truths that had long remained unspoken, although not totally unheard of.

Noli Me Tangere: Mga Tauhan Sinimulang sulatin

Ang pagsusulat ng "Noli Me Tangere" ay bunga ng pagbasa ni Rizal sa

"Uncle Tom's Cabin" ni Harriet Beacher Stowe, na pumapaksa sa

kasaysayan ng mga aliping Negro sa kamay ng mga panginoong putting Amerikano.

Inilarawan dito ang iba't ibang kalupitan at pagmamalabis ng mga Puti sa Itim.

Inihambing niya ito sa kapalarang sinapit ng mga Pilipino sa kamay ng mga

Kastila.

Sa simula, binalak ni Rizal na ang bawat bahagi ng nobela ay ipasulat sa ilan

niyang kababayan na nakababatid sa uri ng lipunan sa Pilipinas at yaon ay

pagsasama-samahin niyang upang maging nobela. Ngunit hindi ito nagkaroon ng katuparan,

kaya sa harap ng kabiguang ito, sinarili niya ang pagsulat nang walang

katulong.

Ipinaliwanag ni Rizal sa kanyang liham sa matalik niyang kaibigang si Dr.

Ferdinand Blumentritt ang mga dahilan kung bakit niya isinulat ang

"Noli." Ang lahat ng mga ito ay maliwanag na inilarawan sa mga

kabanata ng nobela.

Ang pamagat ng "Noli Me Tangere" ay salitang Latin na ang ibig

sabihin sa Tagalog ay "Huwag Mo Akong Salingin" na hango sa

Ebanghelyo ni San Juan Bautista. Itinulad niya ito sa isang bulok sa lipunan na

nagpapahirap sa buhay ng isang tao.

Mga Tauhan:

Crisostomo Ibarra

Binatang nag-aral sa Europa; nangarap na makapagpatayo ng paaralan upang

matiyak ang magandang kinabukasan ng mga kabataan ng

Elias

Piloto at magsasakang tumulong kay Ibarra para makilala ang kanyang bayan at

ang mga suliranin nito.

Kapitan Tiyago

Mangangalakal na tiga-Binondo; ama-amahan ni Maria Clara.

Padre Damaso

Isang kurang Pransiskano na napalipat ng ibang parokya matapos maglingkod ng

matagal na panahon sa

Padre Salvi

Kurang pumalit kay Padre Damaso, nagkaroon ng lihim na pagtatangi kay Maria

Clara.

Maria Clara

Mayuming kasintahan ni Crisostomo; mutya ng

Pilosopo Tasyo

Maalam na matandang tagapayo ng marurunong na mamamayan ng

Sisa

Isang masintahing ina na ang tanging kasalanan ay ang pagkakaroon ng asawang

pabaya at malupit.

Basilio at Crispin

Magkapatid na anak ni Sisa; sakristan at tagatugtog ng kampana sa simbahan ng

Alperes

Matalik na kaagaw ng kura sa kapangyarihan sa San Diego

Donya Victorina

Babaing nagpapanggap na mestisang Kastila kung kaya abut-abot ang kolorete sa

mukha at maling pangangastila.

Donya Consolacion

Napangasawa ng alperes; dating labandera na may malaswang bibig at pag-uugali.

Don Tiburcio de Espadaña

Isang pilay at bungal na Kastilang napadpad sa Pilipinas sa paghahanap ng

magandang kapalaran; napangasawa ni Donya Victorina.

Malayong pamangkin ni Don Tiburcio at pinsan ng inaanak ni Padre Damaso na

napili niya para mapangasawa ni Maria Clara.

Don Filipo

Tinyente mayor na mahilig magbasa na Latin; ama ni Sinang

Señor Nol Juan

Namahala ng mga gawain sa pagpapatayo ng paaralan.

Lucas

Taong madilaw na gumawa ng kalong ginamit sa di-natuloy na pagpatay kay Ibarra.

Tarsilo at Bruno

Magkapatid na ang ama ay napatay sa palo ng mga Kastila.

Tiya Isabel

Hipag ni Kapitan Tiago na tumulong sa pagpapalaki kay Maria Clara.

Donya Pia

Masimbahing ina ni Maria Clara na namatay matapos na kaagad na siya'y

maisilang.

Iday, Sinang, Victoria,at Andeng

Mga kaibigan ni Maria Clara sa San Diego

Kapitan-Heneral

Pinakamakapangyarihan sa Pilipinas; lumakad na maalisan ng pagka-ekskomunyon si

Ibarra.

Don Rafael Ibarra

Ama ni Crisostomo; nakainggitan nang labis ni Padre Damaso dahilan sa yaman

kung kaya nataguriang erehe.

Don Saturnino

Nuno ni Crisostomo; naging dahilan ng kasawian ng nuno ni Elias.

Mang Pablo

Pinuno ng mga tulisan na ibig tulungan ni Elias.

Kapitan Basilio

Ilan sa mga kapitan ng bayan sa San Diego Kapitan Tinong at Kapitan Valentin

Tinyente Guevarra

Isang matapat na tinyente ng mga guwardiya sibil na nagsalaysay kay Ibarra ng

tungkol sa kasawiang sinapit ng kanyang ama.

Kapitana Maria

Tanging babaing makabayan na pumapanig sa pagtatanggol ni Ibarra sa alaala ng

ama.

Padre Sibyla

Paring Agustino na lihim na sumusubaybay sa mga kilos ni Ibarra.

Albino

Dating seminarista na nakasama sa piknik sa lawa.

And the SEQUEL

EL FILI!

El Filibusterismo The word "filibustero"

wrote Rizal to his friend, Ferdinand Blumentritt, is very little known in the

Jose Alejandro, one of the new Filipinos who had been quite intimate with

Rizal, said, "in writing the Noli Rizal signed his own death

warrant." Subsequent events, after the fate of the Noli was sealed by the

Spanish authorities, prompted Rizal to write the continuation of his first

novel. He confessed, however, that regretted very much having killed Elias

instead of Ibarra, reasoning that when he published the Noli his health was

very much broken, and was very unsure of being able to write the continuation

and speak of a revolution.

Explaining to Marcelo H. del Pilar his inability to contribute articles to the

La Solidaridad, Rizal said that he was haunted by certain sad presentiments,

and that he had been dreaming almost every night of dead relatives and friends

a few days before his 29th birthday, that is why he wanted to finish the second

part of the Noli at all costs.

Consequently, as expected of a determined character, Rizal apparently went in

writing, for to his friend, Blumentritt, he wrote on March 29, 1891: "I

have finished my book. Ah! I’ve not written it with any idea of vengeance against

my enemies, but only for the good of those who suffer and for the rights of

Tagalog humanity, although brown and not good-looking."

To a Filipino friend in

Inevitably, Rizal’s next letter to Basa contained the tragic news of the

suspension of the printing of the sequel to his first novel due to lack of funds,

forcing him to stop and leave the book half-way. "It is a pity," he

wrote Basa, "because it seems to me that this second part is more

important than the first, and if I do not finish it here, it will never be

finished."

Fortunately, Rizal was not to remain in despair for long. A compatriot,

Valentin Ventura, learned of Rizal’s predicament. He offered him financial

assistance. Even then Rizal’s was forced to shorten the novel quite

drastically, leaving only thirty-eight chapters compared to the sixty-four

chapters of the first novel.

Rizal moved to

Inspired by what the word filibustero connoted in relation to the circumstances

obtaining in his time, and his spirits dampened by the tragic execution of the

three martyred priests, Rizal aptly titled the second part of the Noli Me Tangere,

El Filibusterismo. In veneration of the three priests, he dedicated the book to

them.

"To the memory of the priests, Don Mariano Gomez (85 years old), Don Jose

Burgos (30 years old), and Don Jacinto Zamora (35 years old). Executed in the

Bagumbayan Field on the 28th of February, 1872."

"The church, by refusing to degrade you, has placed in doubt the crime

that has been imputed to you; the Government, by surrounding your trials with

mystery and shadows causes the belief that there was some error, committed in

fatal moments; and all the

Rizal’s memory seemed to have failed him, though, for Father Gomez was then 73

not 85, Father Burgos 35 not 30 Father

The FOREWORD of the Fili was addressed to his beloved countrymen, thus:

"TO THE FILIPINO PEOPLE AND THEIR GOVERNMENT"

El Filibusterismo: Mga Tauhan Ang nobelang "El Filibusterismo" ay

isinulat ng ating magiting na bayaning si Dr. Jose Rizal na buong pusong inalay

sa tatlong paring martir, na lalong kilala sa bansag na GOMBURZA - Gomez,

Tulad ng "Noli Me Tangere", ang may-akda ay dumanas ng hirap habang

isinusulat ito. Sinimulan niyang isulat ito sa

Ang nasabing nobela ay

pampulitika na nagpapadama, nagpapahiwatig at nagpapagising pang lalo sa maalab

na hangaring makapagtamo ng tunay na kalayaan at karapatan ang bayan.

Mga Tauhan:

Simoun

Ang mapagpanggap na mag-aalahas na nakasalaming may kulay

Isagani

Ang makatang kasintahan ni Paulita

Basilio

Ang mag-aaral ng medisina at kasintahan ni Juli

Kabesang Tales

Ang naghahangad ng karapatan sa pagmamay- ari ng lupang sinasaka na

inaangkin ng mga prayle

Tandang Selo

Ama ni Kabesang Tales na nabaril ng kanyang sariling apo

Ginoong Pasta

Ang tagapayo ng mga prayle sa mga suliraning legal

Ben-zayb

Ang mamamahayag sa pahayagan

Placido Penitente

Ang mag-aaral na nawalan ng ganang mag-aral sanhi ng suliraning pampaaralan

Padre Camorra

Ang mukhang artilyerong pari

Padre Fernandez

Ang paring Dominikong may malayang paninindigan

Padre Florentino

Ang amain ni Isagani

Don Custodio

Ang kilala sa tawag na Buena Tinta

Padre Irene

Ang kaanib ng mga kabataan sa pagtatatag ng Akademya ng Wikang Kastila

Juanito Pelaez

Ang mag-aaral na kinagigiliwan ng mga propesor; nabibilang sa kilalang

angkang may dugong Kastila

Makaraig

Ang mayamang mag-aaral na masigasig na nakikipaglaban para sa pagtatatag ng

Akademya ng Wikang Kastila ngunit biglang nawala sa oras ng kagipitan.

Sandoval

Ang kawaning Kastila na sang-ayon o panig sa ipinaglalaban ng mga mag-aaral

Donya Victorina

Ang mapagpanggap na isang Europea ngunit isa namang Pilipina; tiyahin ni

Paulita

Paulita Gomez

Kasintahan ni Isagani ngunit nagpakasal kay Juanito Pelaez

Quiroga

Isang mangangalakal na Intsik na nais magkaroon ng konsulado sa Pilipinas

Juli

Anak ni Kabesang Tales at katipan naman ni Basilio

Hermana Bali

Naghimok kay Juli upang humingi ng tulong kay Padre Camorra

Hermana Penchang

Ang mayaman at madasaling babae na pinaglilingkuran ni Juli

Ginoong Leeds

Ang misteryosong Amerikanong nagtatanghal sa perya

Imuthis

Ang mahiwagang ulo sa palabas ni G. Leeds

According s mga EXPERTS DAW! :

José Rizal's most famous works were his two novels, Noli me Tangere and El Filibusterismo. These writings angered both the Spaniards and the hispanicized Filipinos due to their insulting symbolism. They are highly critical of Spanish friars and the atrocities committed in the name of the Church. Rizal's first critic was Ferdinand Blumentritt, a Sudetan-German professor and historian whose first reaction was of misgiving. Blumentritt was the grandson of the Imperial Treasurer at Vienna and a staunch defender of the Catholic faith. This did not dissuade him however from writing the preface of El Filibusterismo after he had translated Noli me Tangere into German. Noli was published in Berlin (1887) and Fili in Ghent (1891) with funds borrowed largely from Rizal's friends. As Blumentritt had warned, these led to Rizal's prosecution as the inciter of revolution and eventually, to a military trial and execution. The intended consequence of teaching the natives where they stood brought about an adverse reaction, as the Philippine Revolution of 1896 took off virulently thereafter. As leader of the reform movement of Filipino students in Spain, he contributed essays, allegories, poems, and editorials to the Spanish newspaper La Solidaridad in Barcelona. The core of his writings centers on liberal and progressive ideas of individual rights and freedom; specifically, rights for the Filipino people. He shared the same sentiments with members of the movement: that the Philippines is battling, in Rizal's own words, "a double-faced Goliath"--corrupt friars and bad government. His commentaries reiterate the following agenda:[19]

* That the Philippines be a province of Spain

* Representation in the Cortes

* Filipino priests instead of Spanish friars--Augustinians, Dominicans, and Franciscans--in parishes and remote sitios

* Freedom of assembly and speech

* Equal rights before the law (for both Filipino and Spanish plaintiffs)

The colonial authorities in the Philippines did not favor these reforms even if they were more openly endorsed by Spanish intellectuals like Morayta, Unamuno, Margall and others.

Upon his return to Manila in 1892, he formed a civic movement called La Liga Filipina. The league advocated these moderate social reforms through legal means, but was disbanded by the governor. At that time, he had already been declared an enemy of the state by the Spanish authorities because of the publication of his novels.

POETRY...EMONESS.... Huling Paalam Salin ito ng huling sinulat ni Rizal nguni’t walang pamagat. Sinulat niya

ito sa To the Philippines Rizal wrote the original sonnet in

Spanish Our Mother Tongue A poem originally in Tagalog

written by Rizal when he was only eight years old Memories of My Town When I recall the days Imno sa Paggawa Salin sa tulang “Himno al Trabajo” na

sinulat ni Rizal sa kahilingan ng kaniyang mga kaibigang taga-Lipaa, Batangas

upang awitin sa pag-diriwang dahil sa pagiging lungsod ng Lipa. Inihandog niya

ang Kundiman Truly hushed today A Poem That Has No Title To my Creator I sing Ang Awit ni Maria Clara Ang tulang ito'y matatagpuan

sa Noli Me Tangere ang inawit ni Maria Clara, kaya gayon ang pamagat. Ito’y

punung-puno ng pag-ibig sa bayang tinubuan. Sa kabataang Pilipino Salin ito ng tulang “A La

Juventud Filipina” na sinulat ni Rizal sa Unibersidad ng Santo Tomas noong

siya’y labingwalong taong gulang. Ang tulang ito ang nagkamit ng unang

gantimpala sa timnpalak sa pagsulat ng To Josephine Rizal dedicated this poem to Josephine Bracken, an Irish

woman who went to Dapitan accompanying a man seeking Rizal's services as an

ophthalmologist. Education Gives Luster to Motherland Wise education, vital breath To Virgin Mary Mary, sweet peace, solace dear Sa Aking mga Kabata Unang Tula ni Rizal. Sa edad 8, isunulat ni Rizal ang una niyang tula ng

isinulat sa katutubong wika at pinamagatang "SA AKING MGA

KABATA". Click here to start typing your text |

[Start the Animation (80kB)] The Monkey and the Turtle A monkey, looking very sad and dejected, was walking along the bank of the river one day when he met a turtle."How are you?" asked the turtle, noticing that he looked sad. The monkey replied, "Oh, my friend, I am very hungry. The squash of Mr. Farmer were all taken by the other monkeys, and now I am about to die from want of food." "Do not be discouraged," said the turtle; "take a bolo and follow me and we will steal some banana plants." So they walked along together until they found some nice plants which they dug up, and then they looked for a place to set them. Finally the monkey climbed a tree and planted his in it, but as the turtle could not climb he dug a hole in the ground and set his there. When their work was finished they went away, planning what they should do with their crop. The monkey said : "When my tree bears fruit, I shall sell it and have a great deal of money." And the turtle said: "When my tree bears fruit, I shall sell it and buy three varas of cloth to wear in place of this cracked shell." A few weeks later they went back to the place to see their plants and found that that of the monkey was dead, for its roots had had no soil in the tree, but that of the turtle was tall and bearing fruit. "I will climb to the top so that we can get the fruit," said the monkey. And he sprang up the tree, leaving the poor turtle on the ground alone. "Please give me some to eat," called the turtle, but the monkey threw him only a green one and ate all the ripe ones himself. When he had eaten all the good bananas, the monkey stretched his arms around the tree and went to sleep. The turtle, seeing this, was very angry and considered how he might punish the thief. Having decided on a scheme, he gathered some sharp bamboo which he stuck all around under the tree, and then he exclaimed: "Crocodile is coming! Crocodile is coming!" The monkey was so startled at the cry that he fell upon the sharp bamboo and was killed. Then the turtle cut the dead monkey into pieces, put salt on it, and dried it in the sun. The next day, he went to the mountains and sold his meat to other monkeys who gladly gave him squash in return. As he was leaving them he called back: "Lazy fellows, you are now eating your own body; you are now eating your own body." Then the monkeys ran and caught him and carried him to their own home. "Let us take a hatchet," said one old monkey, "and cut him into very small pieces." But the turtle laughed and said: "That is just what I like. I have been struck with a hatchet many times. Do you not see the black scars on my shell ?" Then one of the other monkeys said: "Let us throw him into the water." At this the turtle cried and begged them to spare his life, but they paid no heed to his pleadings and threw him into the water. He sank to the bottom, but very soon came up with a lobster. The monkeys were greatly surprised at this and begged him to tell them how to eatch lobsters. "I tied one end of a string around my waist," said the turtle. "To the other end of the string I tied a stone so that I would sink." The monkeys immediately tied strings around themselves as the turtle said, and when all was ready they plunged into the water never to tome up again. And to this day monkeys do not like to eat meat, because they remember the ancient story. |